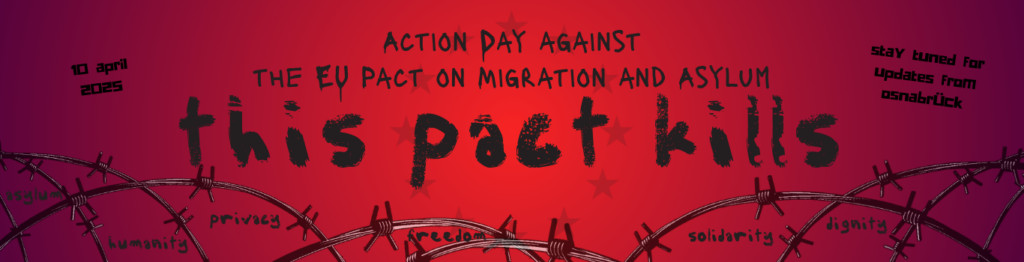

10 April 2025: One year since the EU Parliament adopted the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum.

Why is the new EU Pact on Asylum and Migration dangerous? – Unpack the pact!

1. The EU-Wide ‘Hotspot’ System

Every person arriving at the external borders of the European Union will undergo a mandatory screening procedure, regardless of whether they have applied for asylum. This procedure must be completed within a maximum of 7 days.

People already inside the EU without legal status can also be arrested at any time and subjected to this screening process, which must be completed within 3 days.

During the screening period (3-7 days), individuals are not legally considered to have entered an EU country. This legal “fiction of non-entry” creates legal uncertainty, limits access to fundamental rights and weakens judicial oversight.

Since individuals are not legally on EU soil, they are eectively detained. Anyone who crosses borders irregularly may be arrested, subjected to screening, and deported without having the possibility of requesting asylum.

2. The new Asylum Procedure at the Border

Once the screening process is completed, individuals will either be arrested and deported or allowed to apply for international protection in the country where they first arrived.

The border asylum procedure must not exceed 12 weeks from registration to decision (extendable to 16 weeks in

‘crisis’ situations), during which asylum seekers may be detained and are not legally allowed to enter the country until they

receive a positive asylum decision.

Families with children will not be exempt from border procedures (and detention) but will be prioritized for processing.

What will this new asylum procedure at the border imply?

- People on the move and seeking asylum will be further isolated in border zones, making it harder for organizations to support them and document abuses.

- People will be detained and denied entry while their asylum case is processed. If their application is rejected, they will be deported within 12 weeks, never having officially entered the country.

- More families, children, and vulnerable individuals will end up in de facto detention, with no access to legal representation (only free legal advice).

3. Solidarity à la EU

the pact introduces a mandatory solidarity mechanism among eu states. border countries will continue to be responsible for examining the majority of asylum applications. this means increasing pressure on them and further detereoration of reception conditions and violations of individuals’ rights.

hosting people seeking asylum is not mandatory and the countries can choose whether they want to relocate people or make a financial contribution to first-entry countries or to third countries associated with the EU’s outsourcing of migration control.

With the Pact, more public money will be used to fund walls, barbed wire, police forces, Frontex, detention

centers, and surveillance and control technologies.

The Pact will not create fair distribution or dignified reception of exiled individuals; rather their rights will continue to be trampled on.

This is not (our) solidarity.

4. Detention: the new Normal

According to the Pact, individuals should only be detained when necessary, as a last resort, and under judicial oversight.

In practice, upon arrival in the EU, people in migration may find themselves deprived of their freedom of movement, or in conditions similar to detention:

- During the screening process at the borders,

- If they need to be relocated to another member state responsible for their asylum request,

- During the border asylum procedure

- During the return procedure, if their asylum application is rejected and they are awaiting deportation.

5. The Extension of Deportation Regime

The EU is outsourcing border controls and rapidly moving towards a reinforced system of mass expulsions.

The pact continues the policy of transferring responsibility for border control to third countries, which are increasingly pressured to sign bilateral cooperation agreements to readmit their nationals and asylum seekers.

In the event of insufficient cooperation of these third countries, the EU Commission will retaliate through restrictive visa measures.

Deportations, often masked as ‘return decisions’, don’t just violate human rights, they can also mean months or even years of detention, depending on whether the home country agrees to take someone back. That’s a direct attack on personal freedom.